The Power in Naming

When the boys were young, I read a book called Far from the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity by Andrew Solomon. (OK. I only read half of the book. It’s almost 1,000 pages and I had young children at the time.) Solomon begins the book by making the point that parents and children share some identities but not all. For example, my husband and I are both white and our children are biological, therefore we share the identity of being white.

Conversely, my husband and I are carriers of the mutated gene that causes SEPN1 related myopathy (a rare subtype of Congenital Muscular Dystrophy) but not affected by the disease. Both of our children are carriers but also affected by SEPN1. They have lived and will live with a physical disability every day of their life. Therefore, I will never know precisely what it is like to have this disease and their type of disability, even though both are a huge part of my life since having children.

This framing has helped me as I advocate for my children and for all people with Rare Disease and disability. It reminds me that I can tell our family story and I can share my thoughts about our story, but I can never speak for my children. As they get older, they may want to tell their story to a wider audience. Maybe not. That is their choice, not mine.

Recently this delineation of identities became a little muddied for me.

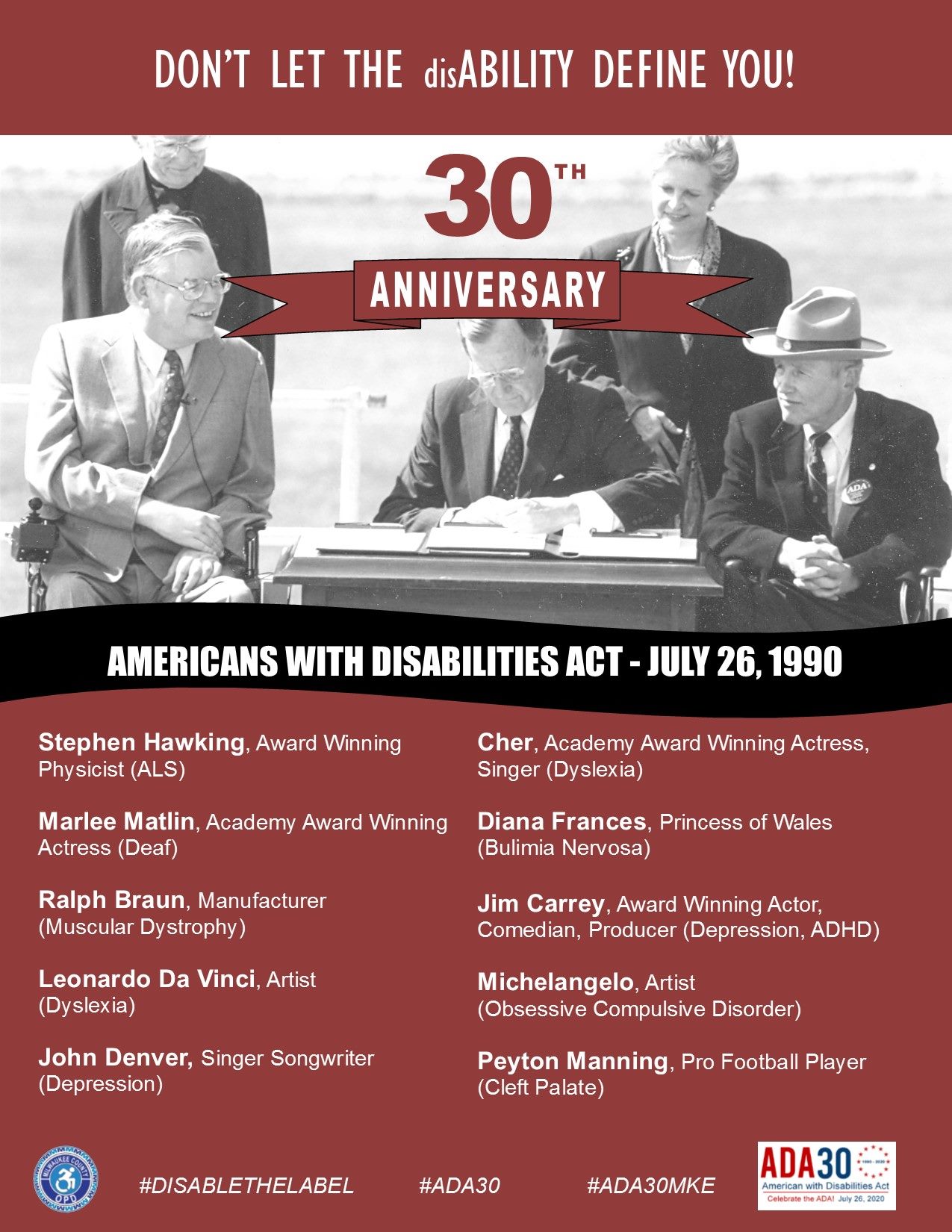

This past July, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) celebrated its 30th anniversary. This law was a turning point in protecting the rights of those with disabilities in the US. I always observe this anniversary, in some small way, because our family has personally benefited from the ADA. But that’s a whole other story. . . . Admittedly, this law is not perfect. We still have a lot of work to do to educate and to advocate for those with disability, but the ADA was a great starting place.

To help celebrate this anniversary, I was tasked by the marketing specialist at work to put together some social media posts. I work for an organization that provides employment to people who are blind or visually impaired, another group of people who benefit from the ADA. As I was searching the web for ideas, I came upon these photos posted on social media by our local office for Persons with Disabilities.

As I scanned them, I thought:

“OK. Stephen Hawking. That makes sense. Physical disability. Huh, I didn’t know Cher is dyslexic. That’s definitely a disability. Ray Charles. Helen Keller. Of course. Duh. But what is this? Abraham Lincoln. John Denver. Depression. Wait a minute. That’s not a disability!”

And then I read this:

To be protected by the ADA, one must have a disability, which is defined by the ADA as a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment. (source: https://www.ada.gov/ada_intro.htm)

See, I have suffered from anxiety and depression my whole life. This truth was hard for me to recognize and admit to myself because (spoiler alert!) these disorders mess with your brain and your view of reality. They have been difficult to navigate, but I’ve never thought of them as being a disability protected by the ADA.

The truth is depression and other forms of mental illness can limit one’s ability to hold a job, care for a family, or even care for oneself. When viewed this way, it makes complete sense that people with mental illness would be protected by the ADA.

So why wouldn’t I think it was when I am intimately familiar with mental illness?

- I’ve always been pretty high functioning despite my anxiety and depression. I have rarely been unable to consistently live a “productive and normal” life.

- I am a product of a culture that has historically viewed mental illness as a moral defect or something the person could have been prevented. As a result, the shame associated with mental illness causes people to keep quiet about their struggle.

- Our culture is more apt to recognize visible disability than “hidden” disability. For example: Person in a wheelchair. Definitely disabled. Person whose mind is stuck in an anxiety thought spiral which makes them unable to leave the house in the morning. They’re just weird.

It’s taken me over 40 years to realize it and admit it, but I have a mental illness that is considered a disability. This realization has caused my world to shift. My struggles feel more valid, like this is a real thing and not just something I’ve made up in my head. In naming it, my perception of myself is different, clearer. Like I’ve uncovered a truth about myself that was always there. “Discovering” I have a disability doesn’t incline me to make excuses or give myself a pass on engaging in life. Rather I am even more resolved to do my best to cope with my mental illness, to take my meds, to use my strategies, and to regularly see my therapist.

Identity and the search for it is complicated, but I’ve decided I will claim this one. I have a hunch it will make me stronger in the end.

There are many wonderful organizations and people working to help those who have mental illness. Here are just a few of my favorites:

- Shine Through: Our local Children’s Hospital created this campaign to help children with mental and behavioral health issues. The website includes great resources for parents.

- Make it Ok: A campaign to end the stigma of mental illness.

- The Hilarious World of Depression: I know, a silly title, but this podcast has help me immensely in recognizing symptoms of my mental illness that I never knew were symptoms. The host recently published an equally wonderful book too.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Reach out for help if you need it. There is no shame in doing so.